Case Preview: PMS International Ltd v Magmatic Ltd

23 Monday Nov 2015

Stuart Brooks, Olswang LLP Case Previews

Share it

The Supreme Court has recently heard the appeal of PMS International Ltd v Magmatic Ltd regarding whether PMS International’s “Kiddee Case” infringes Magmatic Ltd’s Community Registered Design (CRD) for its popular children’s ‘ride-on’ suitcase, the TRUNKI®.

The Supreme Court has recently heard the appeal of PMS International Ltd v Magmatic Ltd regarding whether PMS International’s “Kiddee Case” infringes Magmatic Ltd’s Community Registered Design (CRD) for its popular children’s ‘ride-on’ suitcase, the TRUNKI®.

This will be the first time the Supreme Court has heard a case involving the application of Community Registered Design law, and is likely to have important repercussions for the creative industries. In particular, the judgment is expected to clarify the way that certain design conventions used in CRDs should be interpreted, an issue which has been decisive in a number of important Court of Appeal decisions.

Background and High Court Decision

The validity and scope of protection enjoyed by a CRD is not examined until an owner seeks to enforce it. This assessment requires consideration of a number of interdependent factors. Firstly, the design’s validity is assessed – it must be new and have individual character when compared to any existing designs. Then, the level of design freedom available to the designer and any similarities between the design and any existing designs determine the scope of protection conferred.

Similar considerations determine whether the CRD is infringed by a product. A court will find infringement only if the product does not produce a different overall impression to the CRD, judged from the perspective of an “informed user”. The informed user is deemed to be knowledgeable in the relevant design field and able to make a side-by-side impression. The court must take into consideration the way that the particular design is intended to be used and interacted with, which may lead to certain design features having greater influence on the overall impression than others.

In the first instance decision, the High Court first concluded that Magmatic’s CRD was valid. It recognised that the CRD, which was filed in 2003, shared design elements with an earlier prototype exhibited by Magmatic in 1998 [see Fig 1]. However, since Magmatic’s CRD was was more sculpted and modern, it produced an overall impression which was different from the 1998 prototype, and thus met the validity threshold.

The High Court then compared the Magmatic CRD to the defendant’s Kiddee Case, disregarding the design aspects which the CRD shared with the 1998 prototype (since these were not ‘new’). The High Court found that the Kiddee Case and CRD shared a number of prominent similarities (including a more sculpted and rounded design, and animal-like features) which were not featured in the 1998 prototype. It held that the Kiddee Case did not create a different overall impression from – and therefore it infringed – Magmatic’s CRD.

PMS appealed to the Court of Appeal on the grounds that the High Court had incorrectly interpreted the CRD and improperly excluded various elements of the  Kiddee Case from the design comparison.

Kiddee Case from the design comparison.

Lord Justice Kitchen, giving the leading judgment, allowed the appeal and reversed the High Court’s decision.

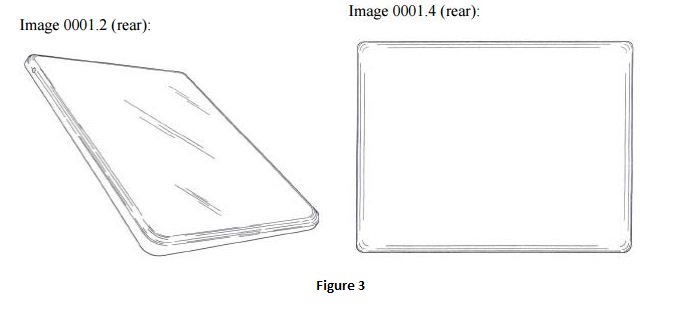

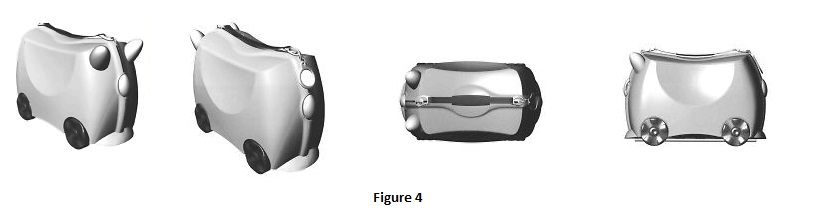

A significant aspect of the High Court’s decision was that it compared only the respective shapes of the CRD and the Kiddee Case, ignoring the surface decoration of the latter. The decision refers to potentially conflicting decisions on this point: On the one hand the Court of Appeal found, in Procter & Gamble [2007] EWCA Civ 93, that an aerosol can represented in black and white line drawings [shown at Fig 2] was deemed to cover the shape shown in the images. In that case, the surface decoration of the infringing product was disregarded during the comparison. On the other hand, the Court of Appeal sanctioned the High Court ruling in Samsung v Apple [2012] EWHC 1882 (Pat) that an important feature of Apple’s design (also being filed in black and white line drawings [shown at Fig 3]) was a lack of surface decoration, which became an important differentiator between it and the alleged infringement.

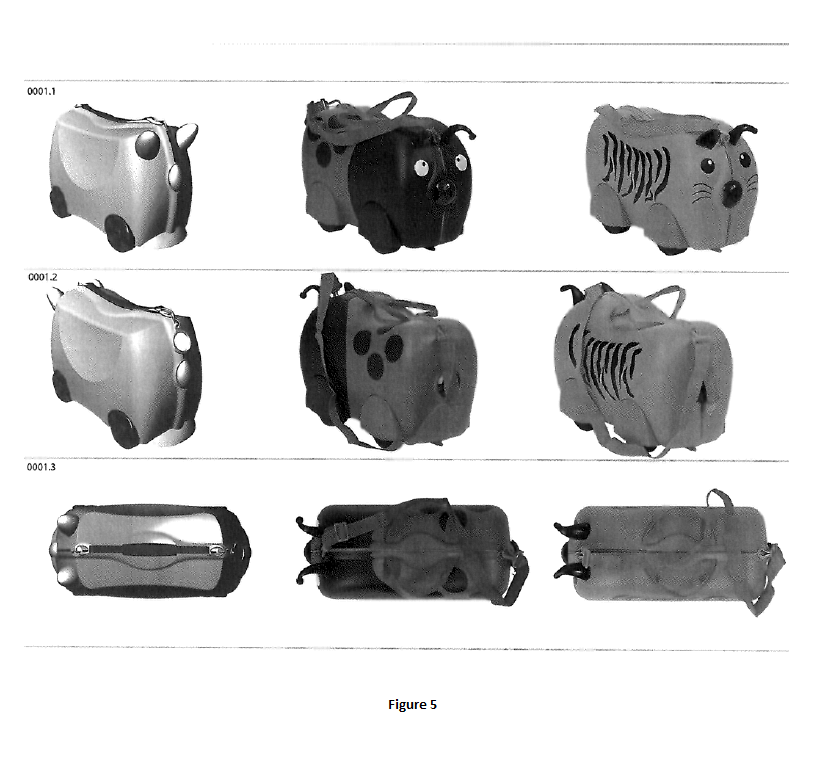

In the High Court’s view, Magmatic’s CRD [shown at Fig 4] did not specify any surface decoration, so was assessed under the Procter & Gamble approach – i.e. that the CRD covers shape only, and should only be compared with the shape (and not surface decoration) of the Kiddee Case. The Court of Appeal interpreted the nature of the CRD differently. In its view, the Procter & Gamble and Samsung v Apple decisions confirmed that the scope of protection conferred by a CRD must depend entirely on the information contained its design images.

Therefore, although the High Court was correct to find that the CRD covered the design in all colours due to its monochrome representation, it wrongly disregarded the colour contrasts contained within the CRD. In the Court of Appeal’s view, the depiction of wheels and a detachable strap in a contrasting colour to the body of the CRD meant that it contained information about its surface decoration. Thus, the Court of Appeal held that differences in the surface decoration of the Kiddee Case and CRD were a relevant factor when comparing the two.

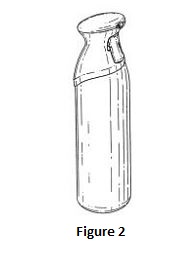

The Court of Appeal went on to consider infringement. In its view, a global comparison could not fail to reveal that the Magmatic CRD created the impression of a horned animal. By contrast, the two Kiddee Case models at issue gave the impression of different creatures: the first of a ladybird, depicted by a two-toned surface with stickers replicating a ladybird’s spots; the second a tiger, depicted by stickers creating ‘stripes’ on its side and ‘whiskers’ on its front. [Both Kiddee Cases are shown at Fig 5].

The Court of Appeal also found that, although there were some general similarities between the CRD and Kiddee Case, several differences between them contributed to a different overall impression, including: (i) the asymmetric profile of the Kiddee Case; (ii) the absence of a cutaway area along the top of the case; (iii) the absence of filled-in wheel arches; (iv) the softer and more rounded shape; and (v) the lack of contrasting wheels.

The Supreme Court Appeal

The Supreme Court now has to consider whether the Court of Appeal erred in law.

In particular, it is expected to provide clarification on whether the colour contrasts shown in the CRD’s computer-aided drawings do in fact operate to limit the design to a particular style of surface decoration. Further, it should consider whether the differences between the Kiddee Case (a product which PMS admitted was at least inspired by the Trunki) and the CRD are sufficient to avoid design infringement.

Those who have adopted similar design conventions will be eagerly waiting to learn how this judgment affects the interpretation of their CRDs, and the resultant scope of their rights.

The progression of the case has been of particular interest to British designers, with numerous stakeholders including the Design owners’ organisation (ACID), and the UK Intellectual Property Office writing in support of Magmatic’s petition for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court. The appeal was heard on 3 November by Lord Neuberger, Lord Sumption, Lord Carnwath, Lord Hughes and Lord Hodge. A full case comment on the decision will be posted once judgment is handed down.

All images are taken from the aforementioned High Court and Court of Appeal decisions.